I’ve worked before with the wonderful Tom Barratt of Tom Barratt Landscape Architecture – he’s a long-time Pique reader and he often has a sense of something that might be a story of interest to me. (This piece on his work in the Chilcotins, which required the long-time road biker to take some mountain bike lessons so he could log hours in the backcountry for the field research, was a favourite: https://craftmtn.com/features/blueprint)

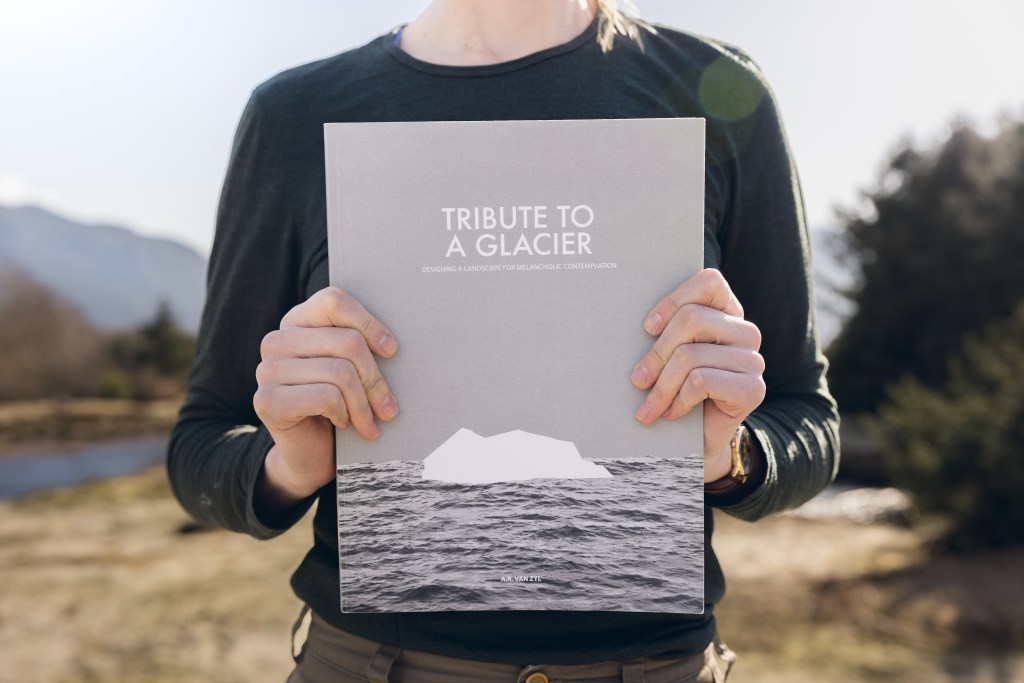

“Mountain culture” has been the obscure little micro niche in a giant media ecosystem that I claimed as my happy place. And through conversations with Tom about different projects, it became apparent to me that landscape architects are among the most unheralded shapers of mountain culture. (And could be deployed far better if our processes were more enlightened, pulling in their systems lens much farther upstream than they’re usually involved.) So when he introduced me to his colleague, Alex van Zyl, who had just been published in an extremely prestigious journal in Europe, I was happy to make the connection. Alex had done a deep dive exploring the role of landscape architecture and design in unpacking our grief and emotions around climate collapse, specifically in respect to the vanishing glaciers. I was in the middle of working through a 7 week course in Active Hope, that spoke directly to the need to unpack grief and hard emotions in response to climate collapse, and it was inspiring to connect the dots between her explorations and mine.

I hadn’t fully appreciated the importance of design of place, until hearing Janis Birkeland speak (as a guest for the Thrutopia series.) The revelation I came away with, from Birkeland’s lifelong devotion to urban design as an agent of change and transformation, is that we might think we are making decisions based on our ideas, thoughts or values, but more often, we’re actually organisms responding to our environment, thinking we’re smarter than everything, not realising how many of our actions are predicated upon the physical and built systems we’re in relationship with.

Anyway, my conversations with Alex have been delightful, and could have yielded a host of different stories.

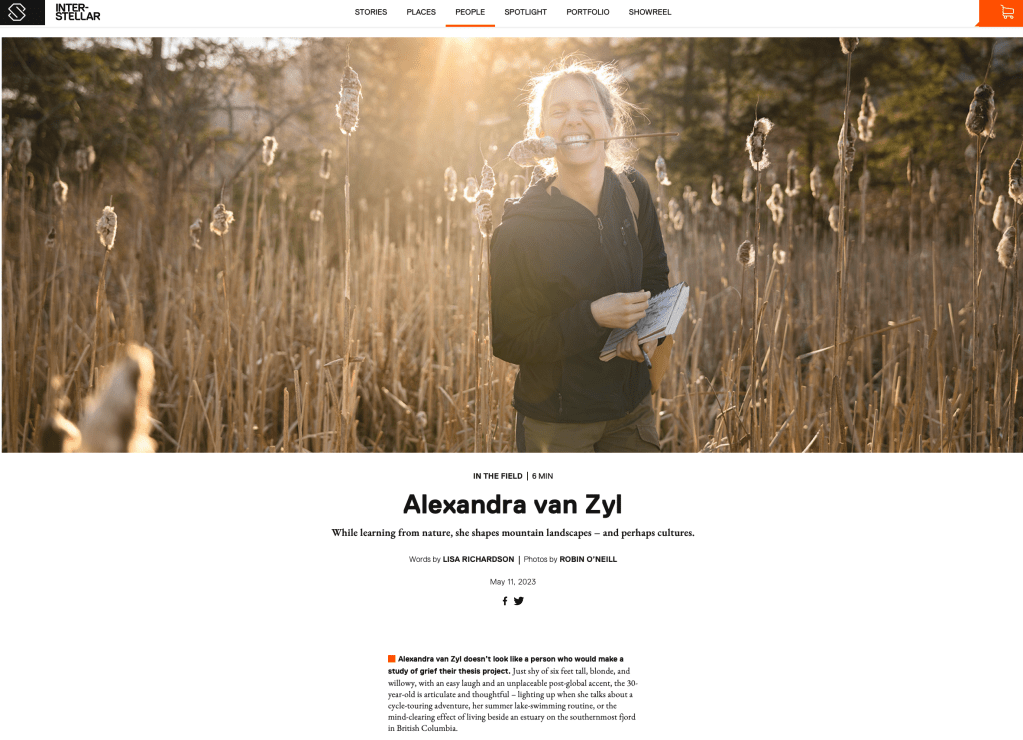

This was the version we got to share with a global audience, thanks to Interstellar Mountain Culture magazine.

Alexandra van Zyl

While learning from nature, she shapes mountain landscapes – and perhaps cultures.

Alexandra van Zyl doesn’t look like a person who would make a study of grief their thesis project. Just shy of six feet tall, blonde, and willowy, with an easy laugh and an unplaceable post-global accent, the 30-year-old is articulate and thoughtful – lighting up when she talks about a cycle-touring adventure, her summer lake-swimming routine, or the mind-clearing effect of living beside an estuary on the southernmost fjord in British Columbia.

But she often thinks about loss and is gut-punched at the thought of glacial retreat and clear-cuts.

“Sadness and grief and guilt give you the ability to feel the lightness. I think you can have a richer experience of place when you can acknowledge the co-existence of joy and loss.”

Alex van Zyl

Van Zyl first thought about glacial retreat while pursuing her master’s degree in science in landscape architecture in the Netherlands. Community members near Switzerland’s Rhône Glacier had taken to tucking fleecy white blankets over the ice in a bid to stave off its rapid disappearance. She was incredulous … and very moved. It propelled her next step — a thesis inquiry that took her to New Zealand to study at the receding toe of Haupapa/Tasman, the country’s longest glacier in the Aoraki Mount Cook National Park and led to the publication last year in one of the most prestigious landscape architecture journals in Europe.

She no longer closely tracks glacial retreats around the world. “Glaciers, for me, are an obvious example of watching something happen because of our highly industrial culture — you feel you can’t do anything about it. How do you navigate that?”

For her part, van Zyl reads the Stoics, practices meditation, and runs along the estuary. “I don’t have all the answers.” But she doesn’t pretend it’s not happening. She’s curious about how we could design better responses.

She gets to indulge this curiosity in her work with Tom Barratt Landscape Architects — the firm that designed Whistler’s iconic Valley trail, a network of valley floor trails that radically de-centred the automobile in Whistler’s early development, connecting neighbourhoods, lakes and parks with pathways that have been imitated and emulated in countless resorts.

Van Zyl’s work is based on the concept that we don’t just shape place. Places shape us. We are constantly influencing each other. Landscape architects are just more intentional about it than most. So when considering the shapers of mountain culture — the athletes, guides, photographers, gear designers and trail builders —we would do well to include landscape architects as key influencers. “We’re in the background thinking of the most meaningful way for people to interact with spaces. Every space you walk through or interact with affects you,” says van Zyl. “You affect each other mutually.”

This was the essence of Darwin’s theory of evolution – the fittest for their place are the ones that survive and flourish. Some are taking this fundamental idea one step further through the concept of biomimicry — a term popularized by self-proclaimed “nature nerd” and biologist Janine Benyus to describe how we can use strategies found in nature to solve human design challenges and foster hope.

This resonates with van Zyl — a woman who has lived in the savannah landscape of Zimbabwe, the below-sea-level cities of the Netherlands, the ski towns of the Canadian Rockies, the most magical places in the world are its alpine environments – the least shaped by the human impact because they’re so inhospitable to our long-term presence.

“There is something about being in a space where everything has to work hard to stay alive. It’s rocky, bare, and rough. You feel quite exposed. The plants are small and tough if there are any plants at all. It’s counter to your daily life,” says van Zyl. “It’s not where I’d go to live but where I go out to seek out the intangible. The quiet.”

The long age of glaciers, the evidence of the primal elements grinding and etching and sculpting entire mountainsides, is an encounter that can right-size us two-footed ones — if we allow our egos to course-correct from conqueror to the fleeting observer, to drop back into the vaster lineage of deep time, where our awe can grow, and our self-importance can shrink. “I think many people feel small when they enter these places,” says van Zyl. In this day and age, that is very, very good. It’s counter-intuitive but a practical prescription for addressing climate grief and human impact. Go to a place you feel small, naturally, such as in the mountains.

###

This story was first published May 2023 at https://www.stellarequipment.com/interstellar/people/alexandra-van-zyl/

Photos by Robin O’Neill. See more of her work at https://www.robinoneillphotography.com and https://www.instagram.com/robinoneill/

Follow Alex van Zyl’s creative work at https://www.instagram.com/avzdrawings/

Very interesting Lisa-thank you.

Sent from my iPad

>