Interviewing Sarah Hueniken and Ines Papert for this story to support the release of their short film Fifty-Fifty was a highlight of last year, not just for the contact inspiration I drew from chatting age milestones with two women who share my birth year, but for time spent connecting with outstandingly accomplished athletes who are also warm, funny, thoughtful human beings.

We make lifestyle choices naively, when we’re young, based on what we think is important, and then we have to test the hypothesis with our actual lives. I think that can be one of the confronting things about “mid-life” – the results of the lifestyle choices are starting to show, in wear and tear, profits and losses. I love that they are still all-in with theirs. And I love that one of their favourite climbing mediums, ice, was such a good metaphor for how we evolve. Young ice, I learned, is brittle, it shatters easily. Mature ice, seasoned ice, is much more reliable. The piece is now live at Arc’teryx Lithographica.

Photography by Klaus Fengler and John Price

For professional climber Ines Papert and mountain guide Sarah Hueniken, 50 is just a number. It’s just one day after 49 — and today you’re the youngest you’re ever going to be, they remind us. What other insights can we glean from two of the most accomplished climbers of our generation?

Building layers

Ice in nature is a living thing.

It doesn’t form like a cube in a tray. It grows from the inside out, in filmy layers, along points of contact — a kind of molecule-by-molecule transference, a pass-it-on articulation of deep cold. Uncontained, it takes shape without a fixed destination, growing from the last point of firmness, slowly bleeding outwards or downwards as gravity plays its part, solidifying into rose petals and cauliflowers and stalactites.

It accumulates.

And to certain geographically clustered, psychologically unique athletes, it beckons, inviting complete presence and promising moment-by-moment transformation.

The lure of ice

“It’s fun to be cold, uncomfortable, and a little scared,” says Sarah Hueniken, extolling without irony the physical extremes of alpine climbing. “To look back on a day in the mountains once I’m enjoying warmth, shelter, and a big meal…it’s euphoria.”

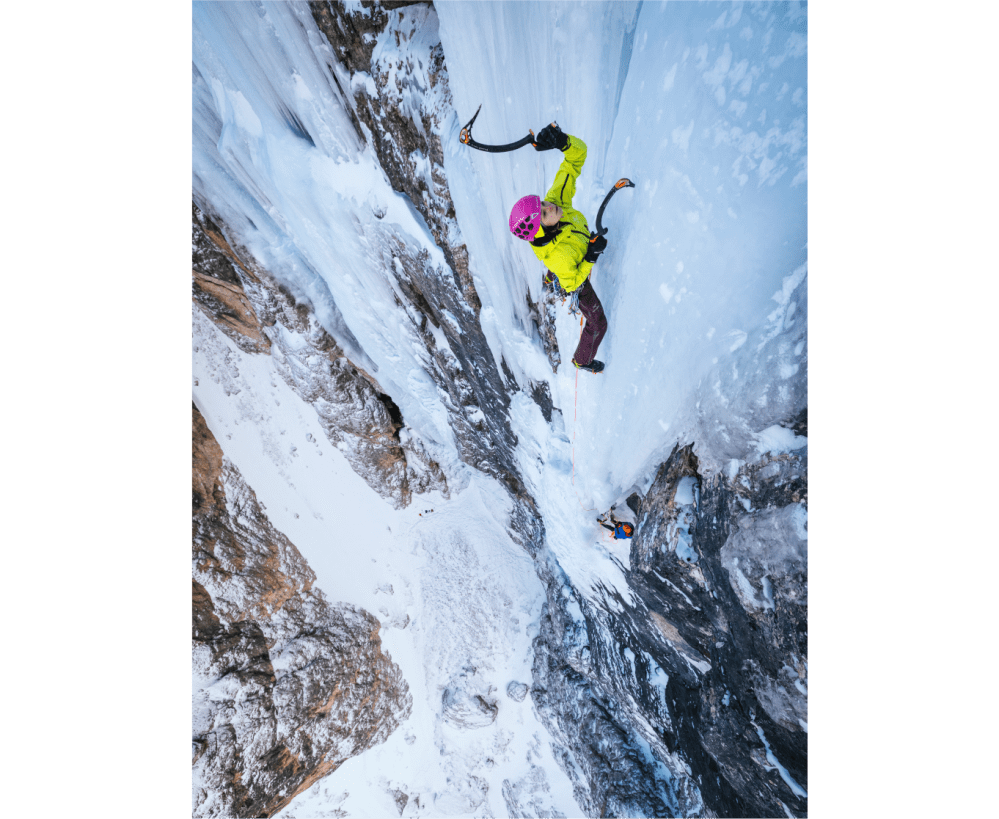

Throughout her 40s, Sarah, now 51, was taking podiums in ice-climbing contests. Already an ACMG alpine guide and examiner and a 5.13 rock climber, she’d gone beyond what any other North American woman had done on mixed rock and ice routes, climbing the grades M11, M12, M13, and M14 — and she was just getting stronger.

“To look back on a day in the mountains once I’m enjoying warmth, shelter, and a big meal… it’s euphoria.”

In 2020, she linked the famed Phobias in the Rockies’ Ghost River Valley combining three hard routes into a single-day 13-pitch mission, something no one has done before or since. The next winter, at the age of 46, in another rarely performed marathon of stamina and skill, Sarah ticked the six hardest lines of the Haffner Cave in a day.

Given the widely held assumption that climbers peak in their mid-20s, she could have made an ice crown, hung up her tools, and called it a day. But why would turning 50 change anything? She’d built a life in the mountains.

And in a climate where the temperatures are sub-zero for more than half the year, she had found her people and her passion. What else was there to do but keep climbing?

Given the widely held assumption that climbers peak in their mid-20s, she could have made an ice crown, hung up her tools, and called it a day. But why would turning 50 change anything?

Prolific first ascensionist and legendary hard-woman Ines Papert turned 51 in April of this year. At 27, the German physiotherapist channelled her love of climbing and her new role as a single mom into the newly established Ice Climbing World Cup. Over the next decade, Ines won four World Championships, 13 single World Cups, and the overall World Cup Series three times.

During the next 25 years, curiosity and ambition propelled her around the world. From Kyrgyzstan to Morocco, Canada to Scotland, Nepal to Norway, she established long mixed routes up to M12 and multi-pitch rock climbs up to 13a. She didn’t slow down through her 40s, establishing next-level routes wherever she went and losing count of how many she developed along the way.

“Maybe 200?” she shrugs. After a certain point, who’s keeping count?

The gift of a climbing life

Over time, life’s feats and defeats, trophies and treasures, accumulate. Without judicious review, they can become clutter.

To celebrate turning 50, Ines hosted a big party, climbed her first 5.14 (8b+), and emptied out her entire garage. “There was so much stuff. Stuff I had been collecting for so many years, which I hardly need at all,” she says. It just wasn’t necessary for her to hold onto it anymore. She kept what was essential and took the time to place things in the hands of others who could use them, moving on with a lighter step.

Ines thinks of fear in the same way — as a weight that can hold you down.

Climbing taught her to always look forward. Now, she knows that failure doesn’t make her less of a climber. It’s what makes a climber.

“Fear can come in, but fear is also allowed to go. Climbing is always connected to failure, always connected to disappointment. And the more difficult objectives you seek, the more chance there is of failing,” she says. “Succeeding is easy — you can always call yourself happy when you succeed. But could you call yourself happy when you don’t? I learned so much from climbing. I learned how to deal with those moments when I thought I wasn’t succeeding and transform them into learnings.”

When Ines was younger, failure felt like evidence that she wasn’t the climber she thought she was. “I didn’t see the advantage of failing. I felt like a loser, like I wasn’t strong enough or lucky enough,” she says.

Climbing taught her to always look forward. Now, she knows that failure doesn’t make her less of a climber. It’s what makes a climber. With years in the mountains under her belt, she’s better able to transform a “failure” into useful information, to ask herself, “What could I do in a different way to make it work?”

There’s always another move, the next hold, a new objective. Each one is a lesson, leading somewhere new.

Always forward

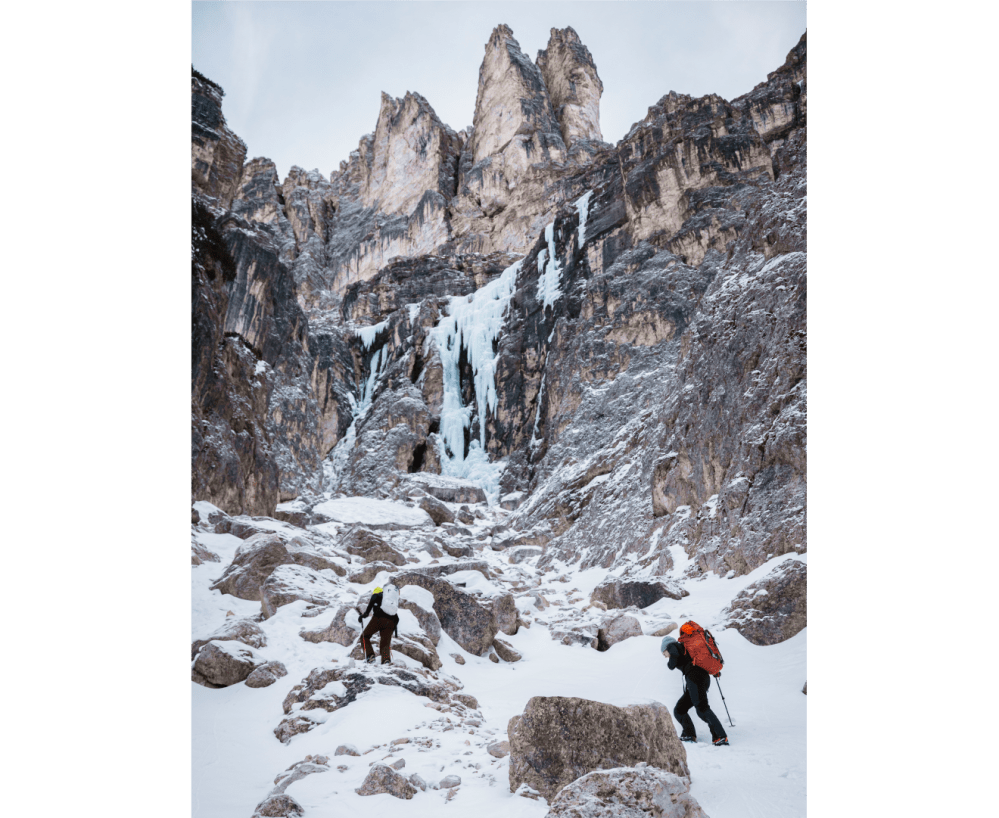

“Don’t look down, Sarah. You have to look ahead at where you want to go. Not back. Just look forward.” Swinging leads on a new multi-pitch in the Dolomites in January 2025 (Hybrid M8+ WI 6 clean), Ines shared one of her trade secrets with Sarah.

Ines’ ability to move into the unknown awes Sarah. Says Sarah: “I’m always thinking, can I go ahead? How bad is this consequence? Do I trust what I’m doing? That whole decision-making process can take so long. For her, it’s natural. She’s like, ‘I know I can do this next thing. I’m just going to move forward with belief and confidence.’ It comes from a place of wisdom and experience. She’s got the back-up for it, but that’s taken years and years to develop. I really admire how in touch she is with what she’s physically capable of doing and what she allows herself to do mentally. Those two are on the right page with each other. That must be a beautiful place to live in.”

While taller than Ines by a few centimeters, Sarah looks up to her 6-months-older comrade. “She’s small, but mighty. Strong and very strong-minded. I would see photos of her in crazy places where I’d never seen other women so comfortable before and think, Imagine being her in that place! It wasn’t about her climbing a certain grade or a certain achievement. It was seeing her level of comfort in these different places that seemed so magical and so unlikely to me. Somehow, this gave me a lot of confidence to push things myself a little bit more.”

“It was seeing her level of comfort in these different places that seemed so magical and so unlikely to me. Somehow, this gave me a lot of confidence to push things myself…”

Having it all vs. Giving it all

Sarah sometimes wonders what would have happened if she’d prioritized being an athlete instead of a guide. She counts her life roles on two hands: daughter, partner, mother, friend, executive director of a non-profit, guide, mentor, athlete. “I want to do all of them. I want to visit my dad in Ontario. I want to take my daughter for a fun shopping day. I want to guide that route that my client really wants me to do. And I want to climb 13d. You can’t make it all happen at the same time, and you can’t be upset about that,” she says.

But she’s stronger now than when she was at 25. Mentally and physically. “I’m smarter. I’ve put more time in. I know myself better. I think I could achieve more now than I could in my 20s, but at the same time, I wish I could take all that learning from life and still have my physical body from when I was younger,” she laughs. “That would be amazing.”

“I’m smarter. I’ve put more time in. I know myself better. I think I could achieve more now than I could in my 20s…”

“I promise I will always climb, as long as my bones allow it,” says Ines. “The type of climbing might change at some point, and the focus on climbing in general might shift, but I’m not just climbing for success. I climb for pleasure and fun. And for the community and people I spend days out there with. So yeah, I hope I can do that for a very, very, long time.”

“The beauty of aging is that your concept of time shifts as you get older,” says Sarah. “At 20, I would have thought that 50 meant it’s all over. Now I see 60-year-olds, 70-year-olds, and 80-year-olds doing stuff, and I think, There’s lots of time left.”

Just like ice builds itself through an accumulation of layers, a life of climbing emerges. Storm after storm, it takes shape, builds bonds, transforms lives — a process of discovering one’s edges and growing beyond them, evolving into something remarkable, something worth celebrating.